John Uttley

THE LAST VICTORIAN AND THE FIRST BABY BOOMER

The home of the author of The Unholy Trinity Trilogy

Where's Sailor Jack? - No Precedent - The Dove Is Dead

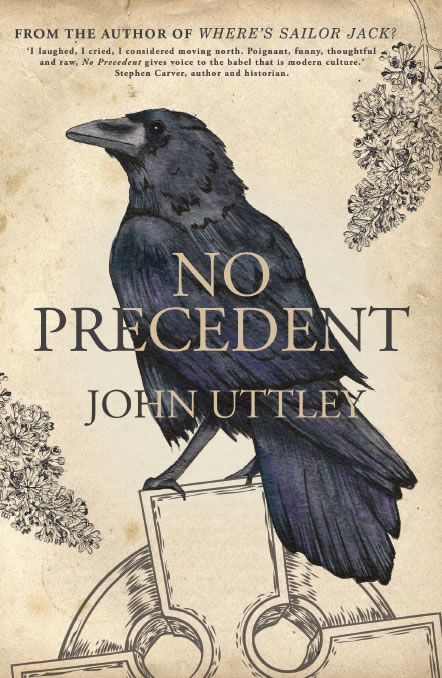

No Precedent

The northern grammar school pals Bob Swarbrick and Richard Shackleton are back, now facing the era of Brexit, Momentum and Donald Trump.

The trials and renewals of Where’s Sailor Jack? behind them, they find themselves in a world whose faith and politics have moved beyond their sphere of influence and feel increasingly cut off from their roots. Bob, now settled with Wendy, must reconcile old memories and new children while Richard must save his family from themselves.

Along the way, they are adopted by the lascivious Lucy Fishwick and her predatory daughter Maddie, whose lives are as mad and chaotic as the radio play Lucy is trying to write and, indeed, the world itself. But despite the coming plague, it doesn’t look like Armageddon.

There is to be an apocalypse, but one of personal dimensions. We don’t all go together when we go!

Book Extracts

I’d better introduce myself, in case anybody ever gets to read this. You never know, maybe I’ll die before I’ve decided it’s best thrown away. It’s going to be as near factual as I can manage, as I’m losing my taste for fiction. Truth’s meant to be stranger than that. I’ve always wanted to write, and something’s happened today which might just end up as interesting. To me that is, probably not to you. I’ve often wondered if telling a real story can reveal a hidden meaning. Maybe this is a chance to see. I’m Bob Swarbrick, born and bred in the Lancashire village of St Chad’s. It’s at the west end of the Fylde, only a few miles outside Blackpool. I don’t live there now, having moved away for the second time a few years ago. My daughter does though, in my old house. I’m often back with my new partner, Wendy. The other folk I visit when I’m home, my mother, father and four grandparents, are all resident in the one place, just a few plots from each other, pushing up daisies in the cemetery at the edge of the village. I’ve a fair number of other relations and a few too many friends in there too. Decades ago, after my divorce and before Wendy and I got it together, I booked a plot for myself, near enough to the gate for me to look for an escape if I’m sent to the wrong place. Behind the funeral chapel, which serves both the quick and the dead, is a lavatory, only for the first category as far as I can tell. I sometimes have to be very quick in getting there nowadays. I’m past my three score and ten, and not too long ago I had a big heart attack, so it may not be long before I’m six feet under.

And there, from the very spot where the grave digger will be digging one day soon, is where I saw him. As I walked the familiar path from my parents to my grandparents, we were nearly close enough to each other for recognition to become possible. He was wearing an unnecessarily heavy black overcoat. In silhouette, he could have been the grim reaper if only he’d been carrying a sickle. The air was actually quite warm and there was enough blue in the sky to give the hope that the Lancashire rain would miss us, but in the distance, behind a fluffy cumulus, I could see a heavily-laden nimbus slowly and darkly plodding its weary way in our direction, like a bladder about to pass its load through an enlarged prostate. He was standing silently by a grave with a shiny headstone. “Grand day,” I said, although it wasn’t really, hoping for some further spur to recognition. And that’s what I got. “You’ve got to be Bob Swarbrick, still seeing the bright side. And that’s after a life more than fully lived, judging by the wrinkles on your face. Am I right or am I right?” he asked. There could only be one answer. “As you always were, you’re right, and after all this time you can still only be Paul Eckersley,” I replied. That wasn’t a totally inspired guess as his surname was inscribed twice on the grave, that of his parents, which, despite a tricky reflection caused by the sun, I’d just managed to read without needing to get my glasses out. A light glaze on my gravestone will be enough, I decided. I don’t go for ostentation. I hadn’t seen Paul or given a moment’s thought about him for fifty-odd years. I looked him in the eyes, up for a scrap I didn’t expect to win. “Is there a knighthood to go with that now? Or a hereditary earldom?” “Neither, Bob. I ended up as a humble housemaster at a minor public school.”

I backed off, feeling guilty. If the headstone was a shade too showy for my taste, it couldn’t be said to represent a wider vanity. Paul’s parents had chosen to come back to Lancashire to be buried. The stone would have been chosen by Paul’s mother anyway, who’d died after her husband, with the lettering amended later to include her. And Paul had followed his father’s footsteps as a schoolteacher. That all felt right and proper. The CBE that I was about to parade was put out of mind. “I bet you were good at that,” I ventured. “Stimulating young minds must be the most satisfying thing you can do. They’d learn bucketloads from you being, should we say, intellectually perverse. And it beats running power stations, which is what I did for a living.” “I know what you did, Bob. You were often on the box or in the papers. You were CEO at Atomic Futures when it was privatised. Until you got fired.” As he said that, the glint in his eye could have been out of malice or humour. After my false start, I decided to assume the latter, or otherwise the conversation would have been terminated, a bit like I’d been, only this time without the legal agreement never to talk about it to friends or strangers. In my year at school, Paul had headed for Cambridge to read English, hoping fervently to sit at the feet of Leavis, rather as his sainted namesake, the writer of the epistles, claimed to have done with Gamaliel, the foremost scholar of his day. My Jewish friends say that if St Paul did indeed so sit, he didn’t learn that much. “Enough,” I answer them, although Pauline theology isn’t always to my taste. Or maybe Paul wanted to do what Bob Dylan did after visiting Woody Guthrie and become the disciple who eclipses the master. Paul’s bad luck meant that he didn’t get the chance to do either.

Leavis left Downing College for pastures new as Paul arrived. Neither of those comparisons work well. I remember the sixth-form Paul riding a bike with straight handlebars and with

three-speed Sturmey-Archer fixed gears. Mine had drop handlebars and a five-speed Derailleur. So, unlike me, Paul didn’t spend the Upper Sixth year freewheelin’ with Dylan. And, even back then, he thought religion was finished. On that, he’s been more with the zeitgeist than me. As an engineer, I’d gone to Imperial, coming home every holiday from the delights and temptations of the Great Wen, as my older sister, already married and with children, would call it. She was too old to be allowed into the sixties. Paul kept on at school for a third year in the sixth so he could apply to Cambridge. Once there, he stayed through most vacations, eventually forcing his parents to move their home to be close to their precious only child. Paul and I had been at odds with each other at school. With me being on the science side and him the humanities, we mainly met in the prefects’ room. He wasn’t a sportsman, nor did he show up at the Church youth club, where most of us went to meet the girls. That he didn’t fancy the youth club was itself unusual. Only Catholics and Methodists didn’t come. They had their own places. But atheists and agnostics weren’t going to pass up the best offer in the village. The way he’d describe religion’s passing with a studied indifference at the school debating society would make me too furious to make a rational response. He would also pour Leavisite scorn on C.P. Snow, who’d suggested that humanity students needed to understand physics, and physicists the humanities. I found Snow’s novels turgid, and I knew he wasn’t considered much cop as a scientist, but his view that renaissance man should try to embrace both was for me beyond challenge. Not so for Paul. Science was for lesser beings. He’d professed to be a Tory at the point when Harold MacMillan was passing over to the fourteenth Earl of Home, just before the white-hot fourteenth Mr Wilson took over Labour. So maybe 1962 was Paul’s Year Zero, although I do suspect that Lord Salisbury would have been his real preference for prime minister.

In other words, I’d always thought Paul was a rum bugger. But then my granddaughter Charlotte, in reality the most conventional of girls, is always saying that our family is far too normal, me included. I don’t think it’s meant to be a compliment. She’d like a more entertaining personal back story to tell. With my long hair, jeans and love of early rock, I’d thought myself then as with it and Paul as definitely without. It’s only with the benefit of hindsight that I can see it could have been t’other way round. The winter of 1962 lasted well into the next year and was far and away the most ferocious in living memory. We were in the Lower Sixth, starting on our ‘A’ level courses. Coming out of that winter, the very late spring seemed like the first one ever on Planet Earth. In the middle of weather bad enough to be considered heavy even on the border line, a little-known Bob Dylan came to London to appear as a hobo folk singer in an oddball BBC play, Madhouse on Castle Street, singing the newly-written ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ over the final credits. I didn’t know anything about it at the time; in our house we were watching Frank Ifield yodelling on Sunday Night at the London Palladium. Later in 1963 though, the year Freewheelin’ was released, my independent world of thought kicked off, just at the point where Harold Wilson was elected Labour leader. I bought the album after a recommendation by John Lennon to the listening public on the Light Programme’s Saturday Club. I couldn’t believe how good it was. I’d constantly replay Hard Rain and was word perfect. I still am. Philip Larkin has duly celebrated the end of censorship, the arrival of the Beatles and the discovery of sex by the end of that cold winter, though the girls of St Chad’s were only ready for the second of those. I was already enjoying the teasing delights of female company at the point I was introduced to Dylan. It was a feverishly exciting time. My older grandchildren, born in the late nineties and so apparently post-millennial, are presently stuck, not for long I suspect, with a Labour leader nobody will ever remember, Ed Miliband, the son of a Hampstead Marxist, who’s as lame as he sounds. Rather than taking any notice of him, they’re usually online playing pretend politics, waiting for an offline world to begin. At school, Paul would affect to like jazz. That had been for my sister’s generation, not ours; she even knew how to ballroom-dance. I loved Victorian hymns though, to me rock’s natural bedfellow as the people’s music. My grandchildren would probably see Paul as more to today’s taste. Like the rest of the country, they’ve given up on religion, despite our best efforts when they were younger.

Seeing the few of us still going each Sunday, forlornly clinging on to our none-too-solid rock, isn’t likely to change their mind. Yet I was brought up in a parochial faith, based on the synthesis of the Wesleys and the Oxford movement, of the Victorian Anglican revival, which still survived in the youth club during my time there. I’m not letting that go. It may be a small part of Christendom, built on shaky foundations, hopelessly split into different factions, marginalised in society, but it’s my Church. In retrospect, I find it surprising, after two shattering world wars containing real existentialist threats to the nation, occupying a quarter of the time between Queen Victoria’s death and my birth, that so little had changed by my childhood. So, by my teens, I assumed it was a culture that would endure eternally. But then, with peace and relative prosperity, things changed quickly. Well-read as she is, Wendy sometimes looks at me in puzzlement at things which seem commonplace to me. She humours me in matters religious, without quite ever exposing her own beliefs to the full glare of ridicule in the way that I do. I’ll be writing this as a story as it goes along, but I doubt that Paul will be the main character, although seeing him has made me uneasy. I hope he doesn’t figure hugely. When I knew him, he usually meant trouble for others and always for himself. As a prophet and not the messiah, maybe he could serve as some sort of John the Baptist figure, a pre-cursor to anything which might follow, though most certainly not one proclaiming the way of the Lord. I’m partly writing this to keep my brain active by the way, as I move into the geriatric phase of life, as well as it possibly forming the notes for a novel I doubt I’ll ever get round to writing. My biggest problem isn’t remembering details, although I guess I could be struggling with that by the time I finish. The problem is sciatica, which is excruciating when I sit down for too long, So, if the prose sometimes reads a little jerkily, then that’s my excuse. And that I studied no English beyond ‘O’ level. Standing there in the cemetery, my problem in moving on to what custom demanded should be discussed next was that Paul had not been that butch a guy, and age had made him sound a shade more camp. “Any family to report, or haven’t you been blessed, if that’s the right word,” I ventured. He knew what I was thinking. His face permitted itself a small smile, before he turned his head so that he was at right angles to me. I could manage to make out that he looked rueful. “No, no wife or children. The fates weren’t kind. Or maybe my critical faculties became over-developed. I was engaged once, and fell in love once, not with the same woman, but both to women, since that’s what you were wondering,” he answered, at first softly but rising to the vehemence I remembered only too well. I wasn’t brave enough to take the issue, or lack of, any further. He hadn’t asked about my family situation. I suppose he knew it already. But since you shower don’t, I’d better tell you. I’ve got two middle-aged children from my marriage to Jane, and two much younger with Wendy. I met Wendy not long after my demise at Atomic Futures, when as a consolation prize I chaired a green energy company that she and another banker, my best friend Richard Shackleton, helped float on the Stock Exchange. She’s saved me from an old age of regret. Nowadays, she’s in big demand to teach on archaeology courses at the local college in Worcestershire, where we live. I can’t marry her as she is still legally married to her first husband, with whom she had no family, entrapped in himself and a nursing home with early onset Alzheimer’s. Alice is aged six and Richie not yet four. They’ve taken her surname, Smith, which I’m very happy about as Alice Smith was my Grannie’s maiden name. As well as the dead of St Chad’s, I’m also visiting the living, my daughter Ruth and her many children, my grandchildren. Wendy is looking after our own kids back in the village of Nether Piddle. Sadly, Ruth has not that long ago been abandoned by her husband for his childhood sweetheart. They’ve divorced. The purpose of the visit is to transfer my old house into her name, now it’s safe to do so without her ex getting his hands on it. I’m also giving my slightly younger son Robert an equivalent sum of money in cash on the grounds of equity with Ruth. It isn’t that he needs the dosh as a top city lawyer. He’s told me to give it all to Ruth, but I can’t do that. Equity must be equitable unless a statute applies, if I’ve remembered the law right.

I asked Paul instead how long he was up in St Chad’s for, assuming that he, like me, was on a flying visit. I was surprised to learn that he’d just bought a house in the quite posh Little St Chad’s Lane at the edge of the village. Those who succeeded in the postwar meritocracy even at relatively modest levels haven’t been left short of funds. He told me that he’d always liked a circular narrative, and he was coming back to die. Without issue, he added. Part of me would like my story to end where it started too, but the other part is comfortably and firmly ensconced with my second family, including aging dog and cat, in our village, Nether Piddle. (I can’t see that place name surviving much longer without challenge.) It’s always been a thought of mine that maybe the end of time and the beginning are the same place, making a circular narrative tidier. Otherwise, like on a holiday which doesn’t end where it starts, there’s that difficult post-trip stage of going to pick up the car at a different airport. And, if it’s truly circular, all that happens must have been at some level there at the start. I suggested this concept to Paul. “May my death be soon,” he snorted. “Fifty years on and you still come out with the most preposterous notions. And you’ve probably invented some spurious physics to back it up. Eliot nearly had it right. If we contrive at the end of our exploring to arrive back where we started, it will be to know the place for the first time, but only because you can’t view things from the inside.” “That’s part of what I was saying,” I replied. He didn’t take up the cudgels. Surprisingly, he asked if I’d time for a drink. I was due back at Ruth’s for lunch with her family in half an hour, and had been out a while, so I asked if he could manage an hour in the pub sometime in the next day or two. “I’ve nothing else to do, so that would be good,” he replied. “Would you like to meet Ruth? I’m sure Ethel next door could babysit for her,” I offered, thinking I might need Ruth’s conflictmanagement skills. “I’d prefer not. You’ve managed two lots of children. I’ve none. Just us, if you don’t mind, Bob.” It was presumptuous of me to have offered Ruth without asking her anyway. We arranged to meet at half past eight the next night in The Old Tithe Barn, a short walk from Ruth’s. Paul’s new home is a little bit further away, but not much more than ten minutes’ walk. As we each climbed into our cars, spots of rain gently fell on the windscreens, a slow release of pent-up tension from above. As I drove off, the sound of the windscreen wipers drowned out the silent melancholy of the cemetery.

‘A wonderful follow-up to Where’s Sailor Jack? this time told by Bob and Wendy themselves. I laughed, I cried, I considered moving north. Poignant, funny, thoughtful and raw, No Precedent gives voice to the babel that is modern culture, as experienced by a group of very different families who all nonetheless love each other to pieces.’