John Uttley

THE LAST VICTORIAN AND THE FIRST BABY BOOMER

The home of the author of The Unholy Trinity Trilogy

Where's Sailor Jack? - No Precedent - The Dove Is Dead

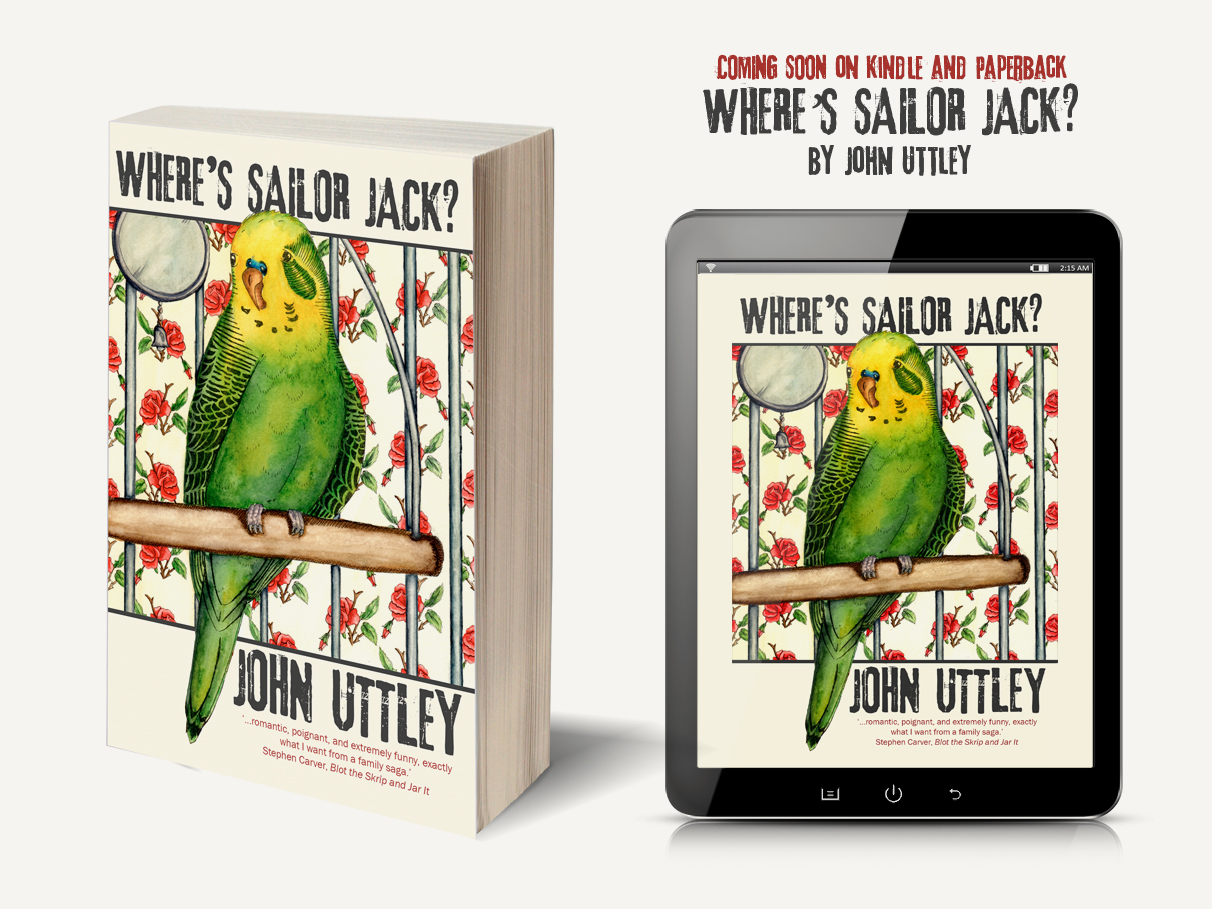

Where’s Sailor Jack?

A novel about first love, lasting love, the purpose of life and the meaning of cricket.

Bob and Richard were part of the one generation of lower class provincials in England ever to get a real shout. Grammar school boys from Lancashire, they’d shared in the great flowering of working class culture from the late fifties to the mid sixties, before rising with the meritocracy in business and industry. By their own admission, they’d taken far more out than they would ever put in.

Now in their sixties, they still occupy their hinterland of church youth club innocence. Richard looks for meaning and Bob purpose. Richard sees events as fickle fate, presently working in his favour, Bob as a catalogue of decisions he’d enjoyed making, with some bad ones currently coming home to roost.

As they look for someone or something to believe in before the last trumpet sounds, both men are to be tested over the next year in life, love and death. Just one thing is for sure: they will be changed.

Book Extract

Family history only makes sense looking backwards. Yet hindsight creates illusions that defy contradiction. With a few peeks in the rear view mirror, this story must go onward and forward. But from when? The end of 1944, with the Christmas leave Petty Officer Jack Swarbrick, from St Chad’s near Blackpool, and Sergeant Michael Shackleton, from Bolton, separately managed to wangle? These two guys never knew each other. The famous cup final between their two towns in Queen Elizabeth’s coronation year, when Bob Swarbrick at the age of seven and a half first watched television and Richard Shackleton, two days younger, made the trip to Wembley? At that young age their illusions were of the future.

The two boys weren’t to meet until forty years later, Lancastrian red roses cresting their caps, when their career paths crossed in the privatisation of Atomic Futures. Engineer Bob was Chief Executive of the company and Investment Banker Richard led the multi-billion flotation for Grindleton’s. A decade further on again, the roses were beginning to wilt. Richard was struggling to keep his job after a row with his Chairman, Sir Charles Norman, coincidentally Bob’s nemesis a few years previously. Their time of being in the thick of it was up. Their catch-up lunch in a dark cubicle of a dingy steak restaurant in Smithfield was subdued. That’s where to begin, well through their story of life, with their dreams in the past, the back fold of the dust jacket the more practical bookmark.

Following over-generous alcohol intake in his thirties, which fortunately had left no lasting damage, Richard was teetotal. His companion had to order by the glass. Bob was morosely finishing his second. The cricket season had just finished with Lancashire again finishing runners-up. For this, Richard blamed his Dad, who’d begun the affair that wrecked his marriage back in 1950. “That’s when we cocked the last game up and only shared the damn thing with Surrey. The Almighty’s had it in for us ever since.”

“The sins of your father shouldn’t be visited on me too,” felt Bob. “My Mum and Dad were happily married. Mind you, I’ve not been entirely blameless since Jane divorced me.”

Richard confessed to transgressions in the years between, before he met his wife Helen. “It’s the three of us in series that’s stopped us winning it.”

“Plus the fact that Manchester’s monsoon season is August,” Bob grouched, proud of the Fylde coast’s better rainfall record than most of the county.

“And the rest of the year,” added Richard, in tune with West Pennines persistent precipitation. “Any new woman in your life?”

The drab surroundings led Bob to be more downbeat than his cheerfulness usually allowed. “Not recently,” he said lugubriously. “You’ve had it the better way round, single when young, married when knackered.”

“I don’t know about that. At forty, the weekend before I met Helen, I was still on my own, putting up the Christmas tree with lights, baubles, tinsel, angels and a Father Christmas.”

Bob was unimpressed: “Bloody hell, you’ll be telling me there was a fairy on top next.”

“It was a star. Try to feel the pathos.”

“No dangling chocolates?” Bob asked. “You must have been hungry after all that emoting.”

“No, I’d already eaten them.”

Bob gave a wry grin. He asked Richard how he’d managed to get that far through his life without being snared. Richard admitted to being burnt by an early girlfriend, the first girl he’d made love to, who’d had him on a string for too damn long.

Bob hid well any empathy he might have felt. “I was incinerated by my first shag as well. I got her pregnant with our Ruth and married her.” His eyes gazed soulfully into the distance. “Jane’s still the same girl, and she sure wasn’t the right one. She buggered off to live with a bloody weasel.” He slowly skewered the air with his fork as he searched for the right words. “I don’t think it was because either of us changed that much. The person we become in life is already in us in the womb.”

“In which case, I’m going to be hanged. I was nearly strangled by the umbilical cord,” Richard revealed.

“You’ll be kept in suspense to the end then. Our first days were filled with utility furniture and rationing so we’ll have a gloomy death,” prophesied Bob, who enjoyed playing the Jeremiah. Both were deep-voiced, with Bob’s rasping lead harmonising well with Richard’s gravelly reflections. They’d moved about too much to retain their youthful best friends and, on an occasional basis, they’d become the brothers they’d never had to each other. Together they ran through their memories of queuing for rationed bananas in the forties, and fifties’ family Christmases when the fates allowed. They reached Larkin’s 1963, the de facto standard dating for the end of the old order. Bob was the rocker of the two and didn’t like Elvis being from the old world. He played older brother. Richard sang the first two lines of ‘Girl of my Best Friend’ while he contemplated this, causing Bob to scowl. The two days age gap between them had made a difference. Bob would have sung ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, agreeing with John Lennon that Elvis died when he joined the army. Richard rejected Bob’s earlier dating, mainly because Freewheelin’ had been released not that long after the Beatles first LP, and Dylan became their main man right the way through

Bob had to agree with this. “Us darling young ones really got going then. Sex wasn’t discovered that early though, whatever Larkin thought.”

“Too right. Apart from reading Lady Chatterley, my hand stroking the bit of flesh at the top of Susan Harwood’s stockings was about as far as I got.”

You couldn’t be a baby boomer, according to either of these founder members (despite statisticians making the start birth date for the category three months after they were born), unless you listened nostalgically to Buddy Holly to remember when you were learning the game.

“One way or another, we learnt it, kid,” Bob was brave enough to say. Richard wasn’t that cocky, not having been able to roller-skate. Bob had fewer doubts about his competence. “I never could jive. What the hell! I can do simultaneous equations.”

“Did that pull the girls?” Richard enquired, eyebrows ironically raised in the middle, one of his winsome tricks. “Not in an all-boys school,” Bob had to reply. Richard recalled his teenage years, when the smell of floor polish at the Church youth club, blended with a hint of disinfectant from the lavatories, competed for supremacy with the aroma of the generously-scented soap the girls had used, if sparingly, at bath time. Bob had similar memories and suggested that they both could have done with something more earthy, losing their virginity earlier.

“It’s who we are,” Richard propounded. “We’ve invented our own hinterland, a bit like Graham Greene did. Ours has never become fashionable with society girls though. It’s Anglican innocence rather than Catholic guilt.”

They looked up as an immaculately feather-cut blonde head giggled at what she heard as she was passing with her partner, a guy who had public school banker swagger sewn into the seams of his suit. As he chivvied her along, she planted her feet firmly down alongside the table and asked, “Still too mean for the Waterside Inn, Bob?”

The head belonged to Rebecca Moore, the very svelte, delightfully cool, former PR Director of Atomic Futures. The swaggerer was her husband rather than a business acquaintance. Despite its unpretentious name, the Inn in question is the great Roux confection on the Thames at Bray. Bob explained to Richard that Rebecca’s dig was caused by a claim for a meal for two she’d put in on her expenses. Richard had eaten there too, and he said the black pudding had been nearly as good as the ones of his youth at the Art Deco UCP restaurant in Bradshawgate.

Rebecca’s shining eyes tilted at his inverse snobbery. “You’d have had no idea what Art Deco was when you lived in whatever one-horse northern town that’s in. You’re worse than Bob. He summoned me up to his office to ask if the local Little Chef had been shut. I enjoyed telling him the Chairman had insisted that’s where we were going.”

Smoothie-chops husband frogmarched her to their cubicle. Bob’s eyes too often looked that way over the rest of the meal. Richard had also detected that Rebecca’s eyes had glowed too much while she’d been looking at Bob. He couldn’t resist finding out more about the rumour that the two of them had been walking out together during the flotation. “Well, maybe,” was Bob’s response. Richard asked why it didn’t work out seeing that they’d looked like great chums.

“She finished it,” admitted Bob. “We were chatting about all this postmodern, structural stuff you intellectuals are into and she gave me a book to read. I quite liked it.”

Richard was sceptical. “No, you didn’t. You wanted to impress your way into her knickers.”

“Don’t judge me by your standards with Susan Harwood,” Bob retorted. “Having offered up my innocence I got repaid with scorn, as our main man found out. I said something too concrete by way of interpretation. The look on her face came from the same pattern in her brain as when she wanted to be sick.”

“Helen specialises in that look. It’s generational, not personal,” Richard confided unconvincingly.

Bob wasn’t persuaded either. “I tried to recover by suggesting that we do have a bit of free will in the scheme of things, the way characters in a novel pull on the author. She argued that there was no author of a book at all and finished with me that evening. She married that master-of-the-universe banker she’s with, who designs derivatives of derivatives, and has an even more tenuous grasp of reality than she does.”

Richard guessed that the offending book was Mythologies, which he said should also be the description for derivatives on bank balance sheets. “It was a bit paradoxical if her thinking she had no agency was her reason for dumping you.” He looked across towards Rebecca before carrying on with his musings. “Not that I’m sure we’ve any either, as you know. We can enjoy the roller coaster but have no choice where it goes. What we can do is think whatever we want to afterwards. I guess that’s better than nowt.”

At their age, making sense of life was mugging up for finals. Only their children and finding comfort in the love of a good woman (or failing that, in Bob’s case, a bad one) mattered more. Their kids weren’t in the restaurant and Rebecca was taken. Richard was about to add that you were only free when you’d nothing left to lose. He changed tack when he saw Bob again gazing in Rebecca’s direction. Richard’s latter-day problem was having nothing left to win. He believed that ideas didn’t follow any laws but actions were dictated by them. “It’s clearly a law that every ten seconds you look Rebecca’s way,” was the proof of his theory.

Bob guiltily shuffled around in his chair so that he couldn’t see her. “You’re probably right. The non-existent God plays dice and we’re clutching at straws.”

Richard said that conscience was the straw he grabbed at, the bit of him that didn’t come either from carnal desire or the wish to conform. “If there’s anything left after taking those out,” he continued, “it’s always too slow to change anything, and just adds to your regrets further down the line.”

“Perhaps as well,” said Bob. “Wasn’t it free will that turned Satan to rebellion?”

Both of them were cradle Anglicans, who still honoured their faith as middle-of-the-road Churchmen. Richard needed a curator to draw, tend and nurture his spiritual world, his reality. For Bob, God had to have created the cosmos from nothing with an act of willpower or nothing could ever be changed by creator or created. Like St Paul, they’d both been untimely born. Things before Elvis had been staid, and after Sergeant Pepper they’d been stale, apart from their main man and just a few others. The rot set in according to Bob with John Lennon spending days on end in bed with Yoko. A few years later, his then wife Jane had made him listen to a Yes album. His growled view of Prog Rock that he’d rather listen to bloody Mantovani anticipated what punk rockers were also to think. Richard had tried to join in the seventies by growing a Jason King moustache, which he’d never quite managed to get the same length either side. He’d worn the polyester suits too, but they’d made his underpants stick to his bollocks. When the women’s movement and disco music came along, white, non-jiving, northern males were what they replaced first. The grammar schools coming and going had cut the two of them adrift permanently from the previous and following generations, by first educating them and then having them think it meant something.

The waiter came and took orders for two tarte Tatins and coffees. Neither cared that much for tatty tart, and wouldn’t pretend they preferred rock-hard fruit in puff pastry to sweet, mashed-up Bramleys in a shortcrust. When the bill arrived, Richard put down his company credit card. Bob threw it back to him, saying it was his turn to pay. Richard insisted: “Take it. You’ve earned enough money for Grindleton’s in your time.”

“It doesn’t sound from what you’ve said that you’ll be there much longer. Once the press have got hold of a Board Room row, someone has to go. As Charlie’s the other guy involved, that’s you.”

Richard had recently refused a bonus, saying it was too generous, and the incident had reached the FT Diary Column. So when the waiter eventually came, Bob didn’t mind that Grindleton’s paid. Outside the restaurant, a dense black cloud was approaching from the north-west.

“That sky looks ominous,” warned Richard as he checked that his umbrella was in his briefcase. Bob raised his collar. “Aye, it’ll rain, snow or go dark before morning. Good seeing you again, pal. Maybe one day the Lord will forgive and Lancashire can win it.”

“Next year in Jerusalem,” Richard hoped, expecting the wait to be another two millennia. “You’re looking a bit flushed. Are you OK health-wise, cocker?”

“It’s just the red wine. I’m fit as a fiddle. I need a change of scenery and I’m looking at houses back up in St Chad’s. I’ll be right as rain once I’ve moved back.”

Richard left Grindleton’s within a month of the lunch. He and Helen were comfortably off with substantial savings tied up in investments. He couldn’t be bothered to sort all that out, and there were mouths to feed, human, canine and feline, so he’d lined up a role with Divinity Partners before resigning. He refused a generous termination pay-off on principle.

In the next spring, 2007, Bob moved his main home to a solid Edwardian semi-detached house about a quarter of a mile from St Chad’s square, keeping his London flat for business needs. He and his sister had grown up in the square, along with their dog Rover, above the ironmonger’s store his parents had owned. It had become an off licence. Even so, his return gave him the air he needed, the soft rustle of trees, the cool smell of the dark evening, and the warm afternoon dampness of Fylde fields gently blowing in from the River Wyre. He couldn’t pin down who he was but he did know where he was from.

‘‘…romantic, poignant, and extremely funny, exactly what I want from a family saga.’